Two disaster experts joined the Center for Public Integrity and Columbia Journalism Investigations on Wednesday for a virtual discussion about an overlooked aspect of disaster recovery: survivors’ mental health.

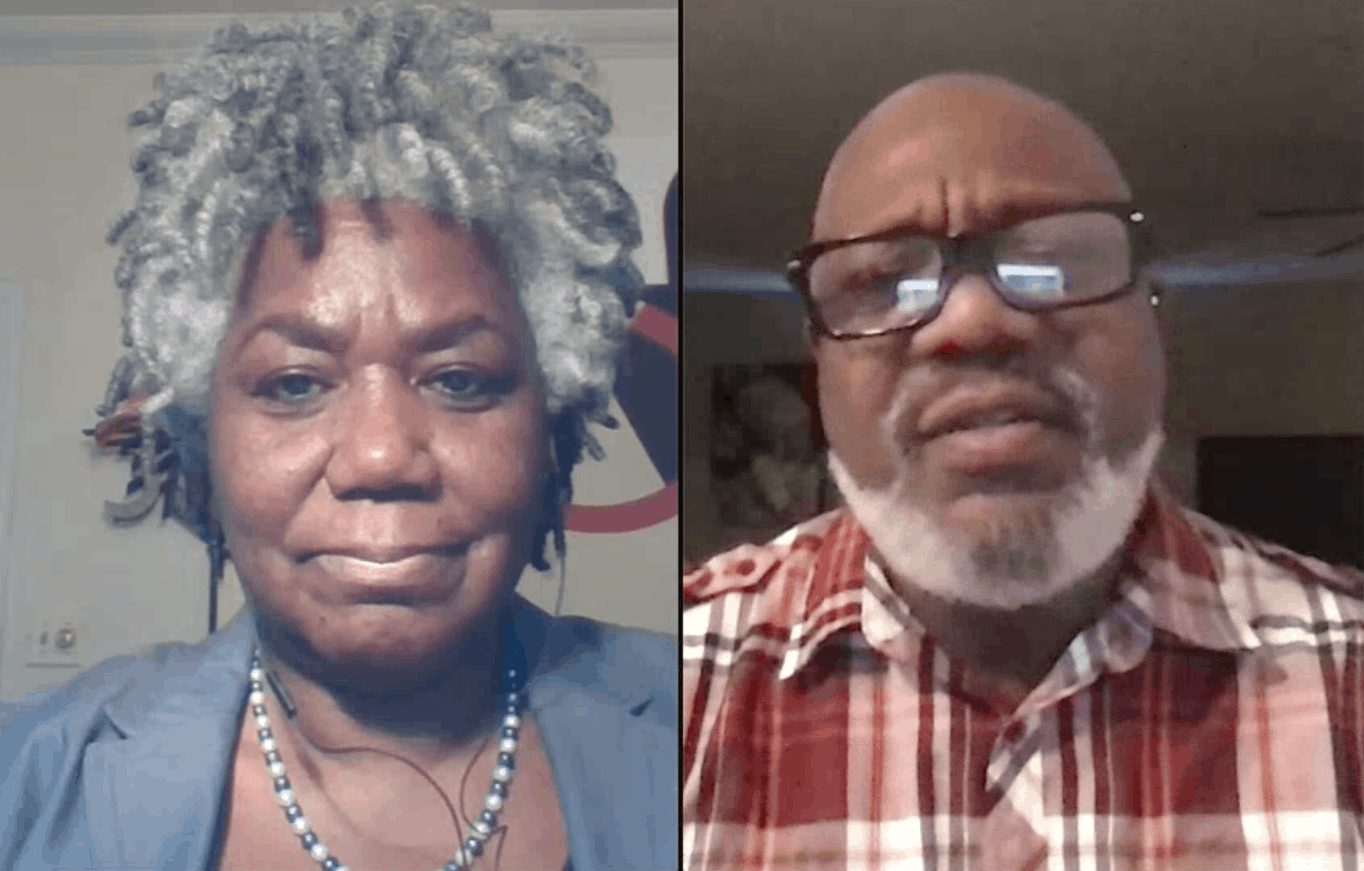

The event was moderated by Jamie Smith Hopkins, a Public Integrity reporter and co-editor of a series about how the country responds to disasters’ mental toll, reported in partnership with CJI and newsrooms around the country. Hopkins was joined by Dr. Annelle Primm, a community psychiatry expert and chair of the All Healers Mental Health Alliance, and Hilton Kelley, an advocate for his community of Port Arthur, Texas, and a survivor of Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

“The stress from a disaster is real and affects everyone, so having that understanding and being patient with each other is really important,” Primm told an audience of people from Florida to Alaska.

Hopkins kicked off the event by asking for examples of impacts people should watch for in survivors following a disaster.

Primm noted survivors may experience anxiety or sadness, and may have difficulty sleeping, eating or concentrating. These symptoms are natural, she said, unless they linger for an extended period of time and interfere with daily life.

The All Healers Mental Health Alliance was formed after Hurricane Katrina. The organization brings together community leaders, health advocates and healthcare workers to come up with “culturally appropriate responses to the mental health needs of people affected by disasters,” Primm said.

Among the immediate coping methods she suggests is to avoid media coverage of the disaster. “Sometimes seeing the disaster play out over and over again can just add to the stress level for people,” she said.

Survivors can also try to restore normal sleep patterns, eat enough food, perform relaxation techniques and stay connected with loved ones, she said.

Kelley, an environmental justice activist and recipient of the 2011 Goldman Environmental Prize, lives on the Gulf Coast and has witnessed government responses to multiple disasters. Too often, he said, people don’t get enough help.

“Instead of being reactive, we should be proactive in these events,” he said. “Our government, local, state and federal, by now should devise a plan of some sort that can help us to understand: How can we be prepared?”

Although seeking mental health support can be critical for survivors, barriers often stand in the way. In Kelley’s experience, the biggest is cost.

“That’s what keeps a lot of us at bay, because the money that you would spend to go and speak to a professional psychiatrist or therapist or whatever, you could be using to help pay the rent,” he said. He also discussed the stigma that some feel if they seek care: “No one wants to be looked upon … as if they’re losing their mind,” he said. “But we have to help people to get around that.”

Both experts said communities of color are more likely to face these challenges. But Primm sees stigma lessening “because people are recognizing that the mental health impact of the sorts of trauma they have gone through is very real.” The COVID-19 pandemic has also increased awareness of the need for mental health, she said, as well as giving people more options to get assistance from their home through telehealth services.

“The country is coming to terms with the issue of mental health,” Primm said.

For communities of color, the psychological toll of natural disasters often layers on top of the traumas that inequality causes.

“A lot of the stressors that we have in our communities are related to systemic racism,” said Kelley. He advocates for clean air in a largely Black and Hispanic area choked by oil and gas pollution, and he spoke on the panel of the impact of police brutality. “Systemic racism lends a hand to the mental health problems we’re experiencing. … It infuriates me, because it’s sad what we’re going through and America stands by and watches it happen.”

So, what can people and communities do to help after disasters? Primm said the keys to improving mental health in the aftermath include restoring a sense of calm and safety, working together, maintaining connectedness and holding on to hope. Her advice: “Make sure that all segments of the community are taken care of, especially the ones that tend to be neglected and overlooked.”

After Harvey flooded his home, Kelley said, he buoyed his spirits by helping others. “It’s good to keep yourself occupied,” he said. “That sort of took my mind off of my own issues.”

This forum is part of a series of online events hosted by Public Integrity, including a Sept. 9 discussion on protecting the right to vote in the upcoming presidential election.