In a stinging rebuke for the Trump Administration, a federal judge in San Diego has given the U.S. government explicit deadlines to reunify more than 2,000 migrant children recently separated from their parents: 14 days for children under 5 and 30 days for kids who are older.

The order issued Tuesday night also requires that officials set up communication between parents and children. It also “preliminarily” bars officials from separating more children from their parents, or from deporting parents until they are unified with children, volunteer to leave without them or are found to be a danger to children.

“The unfortunate reality is that under the present system migrant children are not accounted for with the same efficiency and accuracy as property,” wrote U.S. District Court Judge Dana Sabraw of the Southern District of California in his Tuesday order. Sabraw was appointed by former Republican President George W. Bush.

Trump’s hostile posture toward migrants has divided Americans and sparked debate over constitutional protections, U.S. obligations to international treaties on asylum and the U.S. role in Central America’s troubled history; many of the recent arrivals come not from Mexico, but from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Sabraw’s order is part of the battle over what fundamental rights migrants are entitled to.

In an angry June 24 tweet, Trump said migrants shouldn’t have due-process protection: “We cannot allow all of these people to invade our Country. When somebody comes in, we must immediately, with no Judges or Court Cases, bring them back from where they came.”

Sabraw’s order two days later, though, notes that migrants who filed the suit that led to his ruling argued that separating children violated “substantive due process rights to family integrity under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

Trump had already signed an executive order June 20 to end separation of migrant families and instead put them in detention together, setting off more criticism that Trump was criminalizing migrants fleeing violence and lawfully seeking asylum. In response to Sabraw’s decision, the Justice Department urged Congress to pass legislation that would override two court orders: the 1997 Flores court settlement ordering unaccompanied migrant children be placed in the least-restrictive setting possible and a 2016 appeals court ruling that applied the Flores settlement to families. Congress has struggled mightily with immigration legislation, most recently this week when a comprehensive “compromise” bill went down to defeat in the House.

The 2016 appeals court ruling allowed detention for parents, but the Obama Administration, rather than separating children, began releasing families pending immigration court dates and using monitoring programs—including ankle monitor son adults—in an effort to ensure that migrants actually appeared for their court dates.

Sabraw noted in his order that under Trump, federal officials actually began separating children and parents months ago—before a recent burst of media coverage and before Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ May 7 announcement of a new “zero tolerance” policy that called for jailing and prosecuting all border crossers, including for a first-time misdemeanor. The policy required dividing kids from parents who were supposed to be jailed right away pending trial.

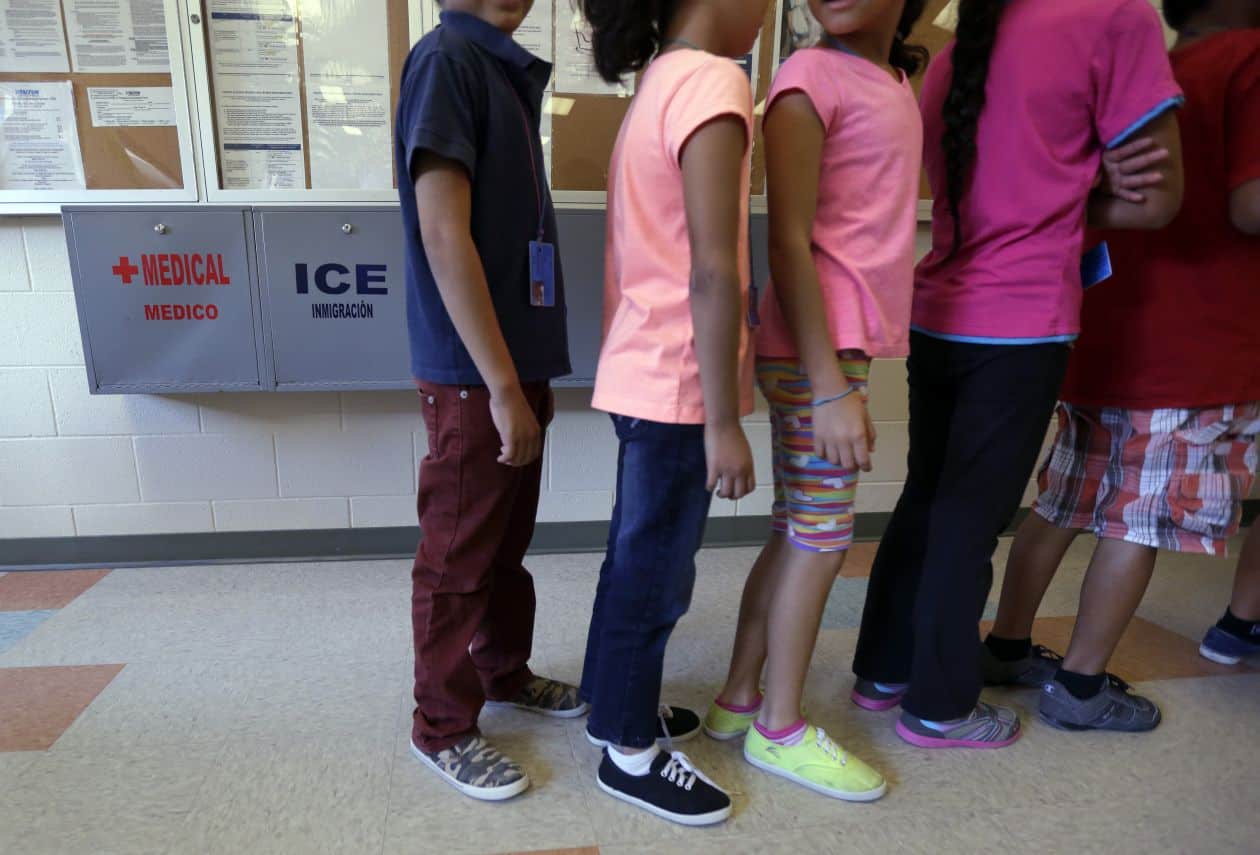

The judge called it a “startling reality” that officials seizing children have an established system for tracking detainees’ belongings but failed to establish an effective system to track children or parents, or a way for them to communicate and reunite after court proceedings. Sabraw also called Trump’s action a “reactive” response to address “a chaotic circumstance of the government’s own making.” He said Trump’s order and other federal officials’ reactions “belie measured and ordered governance, which is central to the concept of due process enshrined in our Constitution.”

Parents who are plaintiffs in the suit from which Sabraw’s order stems demonstrated “irreparable harm,” the judge said, and “the balance of equities and public interest weigh in their favor.”

The case, now a class-action lawsuit, began in November 2017 with a Catholic woman, Ms. L, from the Congo, who entered San Diego’s San Ysidro port of entry with Mexico and asked for asylum, with her daughter, based on religious persecution. After a few days, Ms. L’s 6-year-old child was taken from her mother, “screaming and crying,” and sent to a Chicago shelter more than a thousand miles away; Ms. L and her daughter were separated for five months and only spoke by phone six times.

Joining the case was Ms. C, and her 14-year-old son, Brazilians who were apprehended by Border Patrol agents after illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border and asking for asylum. The boy was also sent to a Chicago shelter, and Ms. C was jailed for 25 days for misdemeanor entry. Because she passed a “credible fear” asylum screening, she was allowed to continue her application and was eventually released on bond.

“Their separation lasted more than eight months despite the lack of any allegations or evidence that Ms. C was unfit or otherwise presented a danger to her son,” Sabraw wrote.

Meanwhile, following the judge’s order, pediatricians who’ve observed separated infants and weeping toddlers inside shelters for separated kids are looking ahead—and this week denounced Trump’s plans to create more detention centers to confine families together until they’re deported or finish legal proceedings. Military bases could host those centers.

“No child, whether infant or a teen whose brain is still developing should be in detention, with or without families,” said Dr. Nathalie Bernabe Quion, pediatrician at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. At a Texas shelter, she saw a toddler sitting by herself sobbing on a bench where she’d been placed on a regular basis due to “meltdowns,” Quion said Thursday.

Advocates are urging officials to release families to relatives or sponsors, and to revive a Family Case Management Program that provided oversight of freed families The Trump Administration ended the program last year. Family detention has been criticized in the past for limited medical services and other problems, as described in a March 2017 paper for the American Academy of Pediatrics. Family detention is also expensive at more than $319 a day per individual.

The American Association of Immigration Lawyers collected data from federal sources indicating that detention alternatives have a strong record of asylum seekers appearing at hearings and check-ins rather than disappearing, which has been a constant complaint of the president’s.

Trump critics say he’s been chipping away at empathy for migrants with rhetoric portraying them in blanket fashion as criminals. He recently used the verb “infest,” which racist anti-immigrant groups often use when describing immigration: “Democrats are the problem,” Trump tweeted. “They don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country, like MS-13.”

A Fox News talk show host said: “Like it or not, these aren’t our kids.”

Before Trump’s presidential campaign, then-Sen. Jeff Sessions, a Republican of Alabama, urged GOP presidential candidates to seize on Americans’ sense of economic woe—and on immigration, including legal immigration. Sessions joined Trump’s campaign, and as the Center for Public Integrity reported recently, used cherry-picked data from one economist and data distortion to spread a fact-challenged message that immigrants have lowered Americans’ wages for decades.

READ MORE:

The Supreme Court’s travel ban decision, explained

Michigan official says migrant kids sent across country without sure way to find parents

What’s behind the policy separating kids from their parents at the border?