This is part of a series,“Model Workplaces, Imperiled Workers,” by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News. The first article is here.

On a December night in 2009, something went wrong with boiler B28 at Valero’s oil refinery in Texas City, Texas. Technician Tommy Manis and his co-workers weren’t sure just what it was. They had tried more than a dozen times to get the boiler started. They weren’t aware of the dangerous levels of gas building up inside, ready to ignite.

Manis had never worked on B28 before. His job took him to different parts of the plant, so he may not have known the boiler’s history: During the previous 15 months, there had been two explosions inside its hulking furnace. After the second, Valero determined gas had built up and ignited. Now, with Manis and his co-workers nearby, gas again flowed unchecked into the boiler.

Oil refineries are inherently dangerous, and the industry’s record of failing to curb hazards prompted the federal government in 2007 to start subjecting them to more intense scrutiny in a special enforcement program. But Tommy Manis and his wife, Laura, trusted that this refinery was safer. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the nation’s chief overseer of worker safety, had formally certified the Valero refinery as a “model workplace” with an exemplary record and an impeccable safety program exceeding that required by regulators.

It was a “Star” site in the agency’s Voluntary Protection Programs — a distinction that, for Valero, conveyed more than just bragging rights. OSHA exempts members of this club, known as VPP, from some inspections, including the special enforcement program targeting refineries and similar initiatives designed to address hazards in some of the nation’s most dangerous industries.

Many of the nation’s largest employers covet the VPP stamp of approval — a mark now held by more than 2,400 workplaces across the country, from sawmills and shipyards to power plants and textile mills. Participation in the program helps reduce injuries and illnesses and lowers workers’ compensation costs, they say. For the Valero refinery in Texas City, it also meant a break on local taxes.

The VPP flag can attract and reassure workers. A red, white and blue symbol of the government’s approval, it flies at nine of Valero’s refineries. Manis had received T-shirts, pens and Christmas ornaments stamped with the program’s logo — gifts from his employer. The refinery’s reputation, his wife recalled, had drawn Manis to apply for the job in the first place: “He thought Valero was the cream-of-the-crop plant. It didn’t blow up. It was safe.”

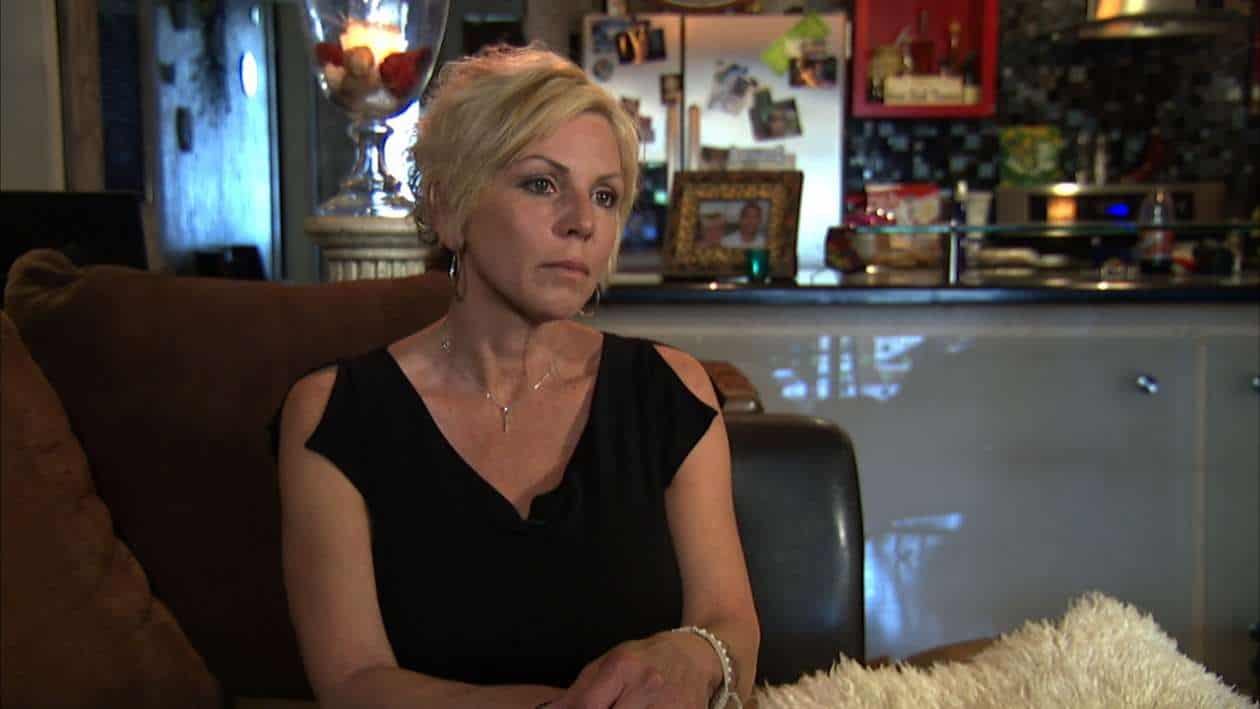

That December night, while in her car, Laura received a text message: Had she heard what happened at the refinery? She knew Tommy was in the middle of a shift. She dialed the sender and asked what was going on. “There was dead silence on the phone, and I knew,” she recalled.

Investigators would later determine that Tommy’s death could have been prevented. Valero hadn’t adequately investigated the first boiler explosion or taken proper steps to prevent it from recurring, OSHA found. The agency determined that the company hadn’t adequately trained workers, evaluated dangers or ensured the problematic boiler conformed to widely accepted safety standards.

Though Valero blames the companies that manufactured and installed the boiler in an ongoing lawsuit, OSHA found fault with Valero, issuing a serious violation and highlighting a half-dozen safety problems. In a June 2010 settlement with the agency, Valero agreed to fix problems at the refinery but didn’t admit to violating safety regulations. The company paid a $4,500 fine.

When the boiler exploded, Tommy Manis became the fourth worker at a VPP “Star” refinery to die since the special inspection progam began in mid-2007. Since his death, three more workers have died at one of these government-recognized refineries. Yet all five plants where the seven workers died retain OSHA’s stamp of approval today, an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News has found. Thus they remain beyond the reach of the agency’s inspection program designed to protect those who work in one of the nation’s most dangerous industries.

Fires, explosions — and exemptions

A similar story line has played out elsewhere: Recognition of “model workplace” status, missed opportunities to detect and fix hazards, a serious mishap or fatal accident, detection of safety violations and, ultimately, continuation of the government’s stamp of approval.

To be sure, there are success stories in the ranks of VPP members — injury rates lowered and workers’ compensation costs reduced, safety lessons learned and disseminated. Even many of the program’s critics believe it could work with adequate oversight. Like other companies in the program, Valero points to a safer workplace and improved employee engagement as the primary benefits of participation.

But agency documents and data and interviews with former OSHA officials, union representatives and experts reveal another side to the program — preventable accidents, unaddressed safety problems and overstretched regulators.

Membership in VPP exempts employers from inspections unless there has been a serious accident, a formal complaint, or an instance in which OSHA learns of a specific potential hazard.

That exemption is perhaps nowhere more beneficial than for sites in industries that find themselves in OSHA’s crosshairs. OSHA’s recent focus on oil refineries offers a clear example of the agency’s approach: Identifying industries where problems seem to be widespread, charging inspectors with policing them, but placing some sites off-limits for special inspections. Roughly 30 “model workplace” refineries are off-limits to inspectors under the program.

Not only have workers died at VPP refineries, those plants appear to have some of the same problems plaguing the larger refining industry.

Fires are a primary concern. Refineries are fuel factories that use highly flammable chemicals. Even small fires can be indicators of how well refiners are managing hazards that can lead to catastrophic explosions or toxic chemical releases. Regulations require companies to evaluate potential dangers, test equipment, and investigate mishaps as part of what is known as “process safety management” — the focus of the OSHA enforcement initiative targeting refineries.

During 2009 and 2010, at least 21 of 55 fires at refineries falling under federal jurisdiction occurred at VPP sites, an iWatch News analysis of regulatory and news media reports found. VPP sites make up about 30 percent of these refineries, so these government-recognized sites have experienced more than their proportionate share of fires.

Some refineries are in one of the 25 states that run their own workplace safety agencies, which the federal government requires to be at least as effective as OSHA. All the state agencies have a version of VPP. Many of these states have adopted the special enforcement program, though data on those inspections are harder to track.

The United Steelworkers union, which represents about 30,000 refinery workers, recently reached a similar conclusion after looking at incident data it had collected and talking with local union officers: Refineries in VPP seemed to be just as dangerous as refineries outside of it. “We didn’t think there was any difference,” said Mike Wright, the union’s health, safety and environment director.

Same company, different scrutiny

The patchwork regulatory system in which OSHA officials can conduct routine inspections and find violations at some workplaces while others are off-limits exists even within companies; oil giants such as ExxonMobil, ConocoPhilips and Valero own both VPP and non-VPP refineries, so some of their plants are shielded from special inspections while others aren’t.

At refineries that inspectors can visit as part of the special enforcement initiative, they frequently have found serious safety violations.

One company — Marathon Petroleum Company — offers an example. It owns four refineries under federal jurisdiction — two in VPP and two not in VPP. During inspections conducted under the emphasis program in 2007 and 2008, inspectors proposed $479,000 in fines for 61 violations combined at two of the company’s refineries, in Texas City and Canton, Ohio.

The agency deemed two of the violations in Canton “willful” — alleging that Marathon either intentionally violated the law or acted with “plain indifference” to it. In Texas City, four “repeat” violations involved citations issued to the company in previous inspections. OSHA later agreed to reduce the severity of the violations deemed willful in the Canton case, and Marathon paid the $321,500 fine. OSHA records indicate the Texas City case has not been resolved.

But as VPP members, Marathon’s two other refineries under federal jurisdiction —in Robinson, Ill., and Garyville, La. — are exempt from similar inspections. Even as the new enforcement program got underway, OSHA was concluding an investigation of a fatal accident at the Robinson refinery. In January 2007, a worker had died after being overcome by toxic fumes.

In that case, investigators found five serious violations. Among other things, OSHA said, Marathon had failed to address some hazards in the unit where the accident occurred, and the company had failed to investigate previous similar incidents. OSHA officials identified the case as a priority under its Enhanced Enforcement Policy, meaning the agency had determined “there is reason to believe that the employer may be indifferent to its occupational safety and health obligations.”

Almost every problem investigators alleged was a violation of the process safety management standard — the same standard that was the focus of the emphasis program and would be the basis of most of the citations at Marathon’s two non-VPP refineries.

According to the OSHA report, one Marathon official “asked about the status of VPP and how OSHA views them since they had a fatality.” The company had little to fear, it turned out. The next year, OSHA reapproved the Robinson refinery as a VPP Star site, allowing it to remain exempt from the ongoing enforcement initiative. In a statement, the Labor Department said Marathon took steps to prevent future similar problems.

The Garyville refinery has also experienced fatal accidents. Since 2002, three workers have died there, though none of the accidents resulted in citations for Marathon. The refinery remains a “Star” site today.

Marathon refused to discuss specific accidents or the OSHA emphasis program but provided a statement that “Marathon is a strong supporter of the VPP program and is proud to have many of its facilities VPP certified.”

More recently, an accident in August 2009 at ExxonMobil’s Joliet, Ill., refinery — a VPP site — injured two workers and released a highly toxic chemical called hydrofluoric acid, prompting an air pollution lawsuit from the state attorney general and citations from OSHA. All of the violations initially alleged — from failing to identify hazards to failing to test equipment and correct deficiencies — related to process safety, the subject of the ongoing emphasis program. OSHA later agreed to delete one of the violations, and the company paid a $9,000 fine.

‘A matter under discussion’

The government’s special scrutiny of refineries stemmed from tragedy. In March 2005, an explosion killed 15 people and injured 180 more at BP’s Texas City refinery, just a short drive from where Manis would die four years later. The U.S. Chemical Safety Board, the independent federal agency that investigated the BP disaster, in 2007 urged OSHA to start a “national emphasis program” that would give special scrutiny to refiners in an attempt to curb hazards before disaster strikes.

OSHA shared concerns about the industry. “As a result of the Texas City accident, OSHA began evaluating its data on fatalities and catastrophes and determined that refineries experienced more of these problems than the next three industry sectors combined,” Richard Fairfax, who headed the agency’s enforcement programs, told a congressional subcommittee n 2007.

OSHA took the board’s advice and started the emphasis program later that year, focusing on process safety management — the control of dangers associated with the use of highly hazardous substances that could lead to fires, explosions or chemical releases. The agency planned to inspect every oil refinery under federal jurisdiction.

Every refinery, that is, except those in VPP.

The industry has been among VPP’s strongest supporters. The current chairperson of the association representing VPP participants works for Valero spinoff NuStar Energy. Two of the program’s staunchest supporters in Congress — Sens. Mike Enzi, R-Wyo., and Mary Landrieu, D-La. — received more than a half-million dollars combined in contributions from the oil and gas industry since 2005, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics. Overall, the industry spent almost $146 million to lobby the federal government in 2010.

Representatives for two oil industry trade groups, the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association and the American Petroleum Institute, did not respond to repeated interview requests for this story. But the president of the refiners’ association, Charles Drevna, did send OSHA chief David Michaels a letter last year, urging continued support for VPP. “There is no need for OSHA to revisit and inspect VPP worksites as part of the Refinery Process Safety National Emphasis Program,” Drevna wrote.

But, to OSHA, that isn’t so clear. “We have had some fatalities in VPP refineries, so that’s something [i.e., the National Emphasis Program] we are still trying to figure out,” said Jordan Barab, the agency’s No. 2 official. Asked if the refineries beyond the reach of the current emphasis program are safer than those that aren’t, Barab said, “One would hope so.”

To make sure they are, he added, the agency is considering inspecting a few VPP refineries. The agency has the authority to do so, but there are other potential challenges, among them a scarcity of resources. The possibility of conducting intensive inspections at VPP refineries, then, is “a matter under discussion,” Barab said.

The refiners’ association, in its letter to Michaels last year, defended the exemption from special inspections. “VPP sites are exempt from programmed inspections because the program has and continues to meet its goal to foster a collaborative environment between management, labor, and OSHA,” wrote Drevna, the association’s president. “NPRA members believe that the exclusion of VPP sites from NEP inspections has not diminished the rigor whereby VPP sites are evaluated.”

The refinery emphasis program, which requires a significant dedication of time and manpower from OSHA, is not the only such ongoing program from which VPP sites are exempt. Since 2002, another OSHA emphasis program has targeted workplaces where hazardous machinery could cause serious injury or death.

The initiative focuses on enforcing a few specific safety standards at workplaces in a range of industries, including paper mills, sawmills, food manufacturers and metal fabricators — all among the largest industries in VPP.

iWatch News identified four fatalities at VPP sites during the past decade in these specific industries that resulted in OSHA finding violations of these specific standards. At least eight other fatal accidents at VPP sites involved the types of hazards outlined in the enforcement program.

Other emphasis programs from which VPP sites are exempt focus on correcting hazards at federal agency sites or ferreting out inaccurate or fraudulent injury and illness recordkeeping.

A relatively new program raises similar issues to those presented by the refinery initiative. OSHA is in the early stages of an emphasis program targeting similar dangers — those presented by the use of highly hazardous substances — at chemical plants. With more than 250 sites under federal jurisdiction, chemical manufacturing is the largest industry in VPP, and all of these sites are exempt from inspections under the ongoing program.

‘Nobody was looking over their shoulder’

By the time Tommy Manis was assigned to work on the troublesome boiler at Valero’s Texas City refinery in December 2009, two of the company’s other refineries had already been inspected under the OSHA emphasis program. Inspectors had found a combined total of more than 30 violations and issued more than $200,000 in fines to Valero’s refineries in Port Arthur, Texas, and Delaware City, Del. (OSHA agreed to reduce the severity of the violations and cut fines in the Delaware City case, and Valero has since sold the refinery. Valero is still contesting the penalties in the Port Arthur case.)

Some believe that OSHA’s findings could have raised red flags. When the last of these violations were announced in June 2009 — less than six months before Manis’ death —George Washington University School of Public Health lecturer and former OSHA official Celeste Monforton raised concerns on a public health blog: “It makes me wonder whether similar violations … would be found at the ‘inspection-exempt’ Valero sites? After all, it is the same employer, the same board of directors, the same executive team and presumably the same safety policies and procedures at its sites.”

Valero spokesman Bill Day said there is a company-wide safety policy that is implemented at every site. “Safety is equally important at all of our refineries,” he said. Eventually, he said, the company aims to have all of its refineries in VPP. “This is a business that has to operate safely in order to attract the best employees.”

Valero, in its lawsuit against companies that made and installed the boiler, states that, because of the “defective package boiler system,” “Valero suffered damages.” Because Texas workers’ compensation laws may shield Valero, Laura Manis’ lawsuit also targets the manufacturers. But she and her lawyer, Gary Riebschlager, blame Valero for the deadly blast.

After the earlier explosions, Riebschlager argues, Valero tried to fix the boiler on the cheap and get it back into service quickly. “All they had to do was fix it right the first time,” he said. “But they didn’t because they knew that nobody was looking over their shoulder.” Once companies qualify for VPP, he added, “they know that OSHA’s not coming in.”

In May 2009 — two months after the second explosion and seven months before the one that killed Manis — OSHA officials had been at the refinery, conducting an on-site evaluation to determine whether to reapprove the site’s VPP status, which had been in effect for almost eight years. They’d chosen to use a “compressed reapproval process,” an abbreviated review reserved for sites that the agency felt had demonstrated excellence.

The evaluation report made no mention of the boiler.

In a statement, the Labor Department said the abbreviated review was “unrelated” to the fatal explosion and had focused on requirements for participation in VPP. “The required programs and processes were in place at the time of the VPP on-site evaluation,” the department said.

It’s far from clear, of course, that aggressive policing by OSHA would have prevented the explosion. Even an intensive inspection like those conducted under the emphasis program is no guarantee that a site is problem-free.

But Kim Nibarger, a safety official with the United Steelworkers, said he sees the Valero accident as an example of larger problems. The explosion, he said, offers more evidence that refineries in VPP aren’t better at managing serious hazards than their non-VPP counterparts, and that the exemption from emphasis program inspections is “cause for concern.”

The family’s lawyer, Byron Buchanan, said interviews with employees who were at the accident scene, along with other evidence, indicated that Rodriguez was overcome by hydrogen sulfide as he and other workers fled a leak of the toxic gas. This gas, a well-known hazard at oil refineries, also killed a worker at Valero’s Texas City refinery in 1998 — three years before the site was approved into VPP.

Valero spokesman Day acknowledged that there was a hydrogen sulfide leak but said the cause of Rodriguez’s death wasn’t yet clear. In court filings, the company denied allegations of gross negligence.

Rodriguez’s employer, Koch Specialty Plant Services, didn’t respond to requests for comment. In court filings, Koch said its liability is limited “because responsible third parties may have caused or contributed to” Rodriguez’ death.

OSHA is investigating the Norco death, and the agency recently closed the Texas City case.

In a statement, the Labor Department said OSHA recently conducted an on-site evaluation of the Texas City refinery.“A decision on the site’s VPP status is pending,” the department said.

Meanwhile, both refineries remain in VPP.

Laura Manis said she hopes her lawsuit will keep Tommy’s memory alive in a meaningful way — by spotlighting safety issues at the countless refineries and chemical plants dotting the Galveston Bay area, including many that are VPP workplaces.

To her, the VPP “Star” logo that adorns the refinery’s grounds is a meaningless trophy: “It says we’re going to give you this little stamp, and you can do whatever you want behind those gates.”